A history of money

Money: what it has been in the past, what it is today, and why it’s not a simple concept to understand...

Everyone I know who bought bitcoin in the early days has a “how did you get into bitcoin?” story.

Here’s mine.

I lived in Buenos Aires, Argentina in 2009. I spent time learning Spanish, exploring the city, sailing the Rio de la Plata, and traveling through neighboring countries.

Argentina has a troubled monetary and economic history consisting of almost a century of high inflation, instability, and debt defaults.

Something you only understand when you see and experience it firsthand is how profoundly “bad money” changes a society. It only changes everything.

Money is a way for society to communicate and coordinate human activity. When money becomes corrupted, the base layer of communication is corrupted. This impacts every other layer built on top of it. Things like trust and faith in market prices, in the government, and in other people you interact with daily, are corrupted too.

Most Argentinians I knew didn’t like to keep savings in the Argentine Peso and they avoided keeping it at the bank, for fear that history would repeat and banks would disallow them from accessing their own money. They would convert their excess pesos into US dollars or gold (stored in briefcases under beds) because they couldn’t trust the institutions meant to protect their money.

These observations made me curious about the nature of money. Specifically, I started to wonder: If Argentina had bad money, what is good money? What are the second-order effects of bad money? What are the second-order effects of good money?

That year I went deep down the rabbit hole of monetary history.

I learned Argentina wasn’t the only country where people didn’t trust the money issued by the government. 20 countries have had currency crises in the last 40 years due to government spending and unrestrained money printing.

I also learned what money fundamentally is, what it has been through history, how our monetary system works, and why the debt-based monetary system we use currently is likely to fail soon.

Little did I know at the time that this research would help me understand Bitcoin when I encountered it in 2013 (and I was initially resistant to it).

With all the monetary theory and history knowledge I had, one would think I would have moved all my investments and savings into Bitcoin when I first came across it. Unfortunately for me, this was not the case.

While studying monetary history, I became very interested in gold. Some of the models we had back then were fairly primitive CTA type models for gold (which actually performed well from 2002-2011) and I mistakenly believed an asset had to have “intrinsic value” to be investable.

After contending with some of the early articles on bitcoin (and there weren’t many good nontechnical sources at the time), I discovered I was wrong and made my first entries in 2014.

We’ll see in the paragraphs below why I was wrong, and how my inaccurate view was the most costly decision I’ve ever made.

Money through the lens of Anthropology and History

“The present is the past rolled up for action, and the past is the present unrolled for understanding.” - Will Durant

My interest in history is motivated in large part by the logic of the Durant quotation above: lessons from history enable us to better understand the present, and to turn that understanding into action.

Most people aren’t familiar with the specifics of monetary history (I know I wasn’t until the last decade ), but it’s important to know if you want to understand how to protect yourself in the future.

Money came about as the solution to a problem.

The anthropological study of money teaches us that money is a technology, first invented to address the problem of retaining multiple different types of reference rates in memory in barter and trade societies.

When societies create and adopt currency, it is to ease negotiation of exchange rates: i.e., what number of x items can be exchanged for what number of distinctly different commodity y.

Not only does this present a huge problem in fluctuating values between x and y, it's also a profound memory challenge. If only 100 different commodities traded then there would be 4,950 exchange rates. Think about what life would be like if we had to do this today, everyday, for every purchase.

Money helped us solve this problem by being a universally desired item we could all trade and exchange for physical commodities we needed to survive.

While money allowed us to specialize and trade more efficiently, it has always required that the people trading it back and forth both believed it to be valuable.

This shared belief that something has value is known as intersubjectivity. Money isn’t useful on its own beyond solving the barter and trade problem. People can’t drink it, can’t eat it, and can’t build structures out of it. The fact that we all agree on its value is what makes it useful.

Money has been created (and recreated) many times, in many places. Money isn’t just coins and dollar bills, and has in fact taken many forms throughout history: beads, shells, jewelry, metal, paper, and digital. Money is anything people use to exchange for something else they need, which brings us back to the exchange rate problem – how do we decide on the value of a chosen form of money?

The first forms of money were some of the best: claim checks to an amount of food. Other ancient forms of money were scarce metals which had social value. Some of these forms of money were easy to copy and create, so they ended up failing over long time periods.

It's worth noting that the more recent form of money - paper currency - is the weakest form of money that has existed because paper currency lacks the ideal properties of good money.

Next we’ll look at the monetary properties and functions of money so we can compare the various forms and decide which one is best.

Functions of Money & Monetary Properties

Good money should be all three of the following:

A store of value - a way to store your wealth without loss over a period of time

A medium of exchange - a way to transact with others in society

A unit of account - a way to account for the value of other items

When we look at history, we see that money is adopted by societies in the same sequence. First, a type of money is selected as a store of value by individuals based on its properties. Next, it is used as a medium of exchange in trade. Finally, once it reaches broad acceptance and adoption, it is used to measure the value of goods and services.

So if money evolves in the same sequence throughout history and starts with individuals selecting it based on its properties, what exactly are those properties?

- Portable - how easy is it to carry around

- Durable - how resilient it is when being used

- Divisible - can you break it down into smaller pieces?

- Fungible - does one item have the same value as another?

- Scarce - is it easy to create new units?

- Verifiable - is it easy to tell if it is authentic?

- Established history - how long has it been used? Who uses it?

All of these properties are important for money to have, but scarcity is arguably the most important property when discussing whether something is a store of value and therefore “money,” or fails to be a stable store of value, which we would consider merely a “currency.”

For example, gold and silver are known as precious metals because they are scarce relative to other metals. That, and it requires a lot of work and human effort to create more supply. Gold and silver have been used as money for thousands of years because they were good money.

People in ancient society selected gold and silver as money due to the fact they were scarce and would pass bars or scraps of gold back and forth in trade. Scraps of precious metal had some limitations however - they were inefficient as a medium of exchange, because metal scraps are not fungible, and are difficult to verify.

Today, it’s hard to imagine a world without paper currency or coins. The concept of coinage began in Lydian society somewhere around 650 BC and it was a massive technological breakthrough.

Coins were easy to transport, didn’t decay, were easily divisible, and fungible - this made trade easier and more efficient. Beyond these properties, coins made from gold and silver were scarce, so unless a government mixed these metals with other less valuable metals, they held their value well over time.

In fact, gold was used to back most major currencies due to its monetary properties up until only recently. Let’s look at the history of how and when that changed, and why the paper currency you carry in your wallet lacks the desirable characteristics of good money.

Using the US Dollar as an example of something we think about as money but that actually fails according to both the functions of money (not a store of value) and is missing key desirable properties of money (not scarce and can be easily created).

The US Dollar wasn’t always backed by nothing - it used to be backed by gold until 1971. Here is a quick summary of key dates and actions taken that led to our current

Gold based monetary systems and US Dollar History:

So is the US Dollar money if it's not backed by gold?

Technically, the US Dollar is a currency, not money, because it functions well as a medium of exchange and a unit of account, but it is not a store of value.

This definition of the US dollar as a currency may come as a surprise to some of you, and maybe the distinction feels a little pedantic, but it has real-world impact. But why is it not a store of value? Governments can (and do) print more paper currency, which dilutes the value of the existing supply.

This results in reducing your purchasing power; the money you may choose to save, if it's not actively earning interest to rival inflation, has less value with each passing day.

Let’s look at a resource that shows exactly how much value it has lost over time:

https://www.officialdata.org/countries

The dollar has lost over 95% of its value since 1913. And this is better than other currencies around the world which have either lost much more value, or have failed completely.

Do you wonder why the cost of everything is going up around the world?

The simplest definition of price inflation is: too many dollars chasing too few goods and services.

The previous chart shows the effect of printing too much money over a long period of time and the ensuing mismatch between an easilty creatable denominator (any currency), and any item you want that is scarce or requires effort and energy to produce.

It's important to point out price inflation is not just the result of money printing. In reality price inflation results from money printing + quantitative easing + poor government policy & spending habits as explained in more detail by Lyn Alden here: https://www.lynalden.com/money-printing/.

With that said, let's look at a few charts which show the historical relationship between currency creation and inflation.

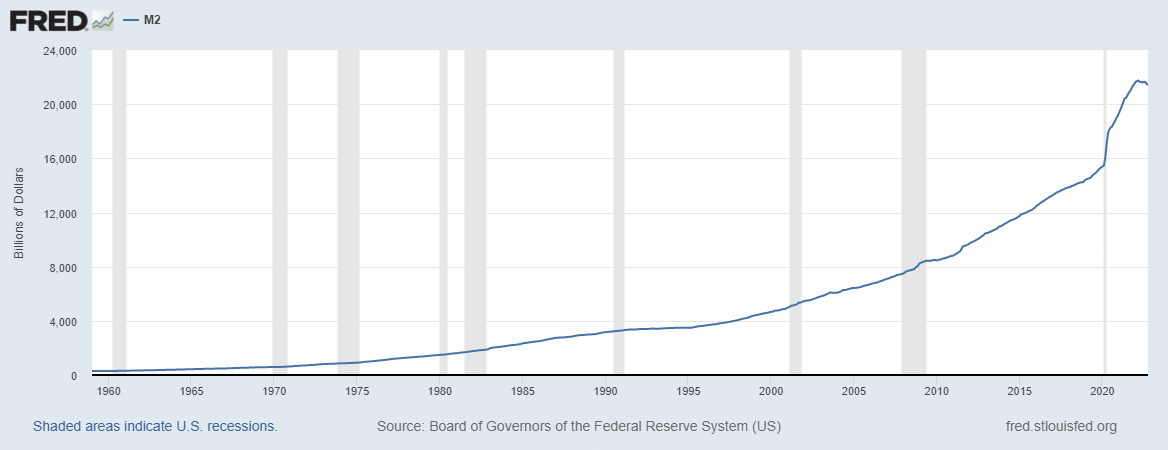

We'll start by looking at M2 money supply growth, a key tool used by economists to forecast inflation, and to measure currency creation. M2 is what we use to measure the total money supply including all of the cash people have on hand, plus all of the money deposited in checking accounts, savings accounts, and other short-term saving vehicles such as certificates of deposit.

Since 2020, we saw M2 money supply expand by 40%.

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/fredgraph.png?g=WIv9

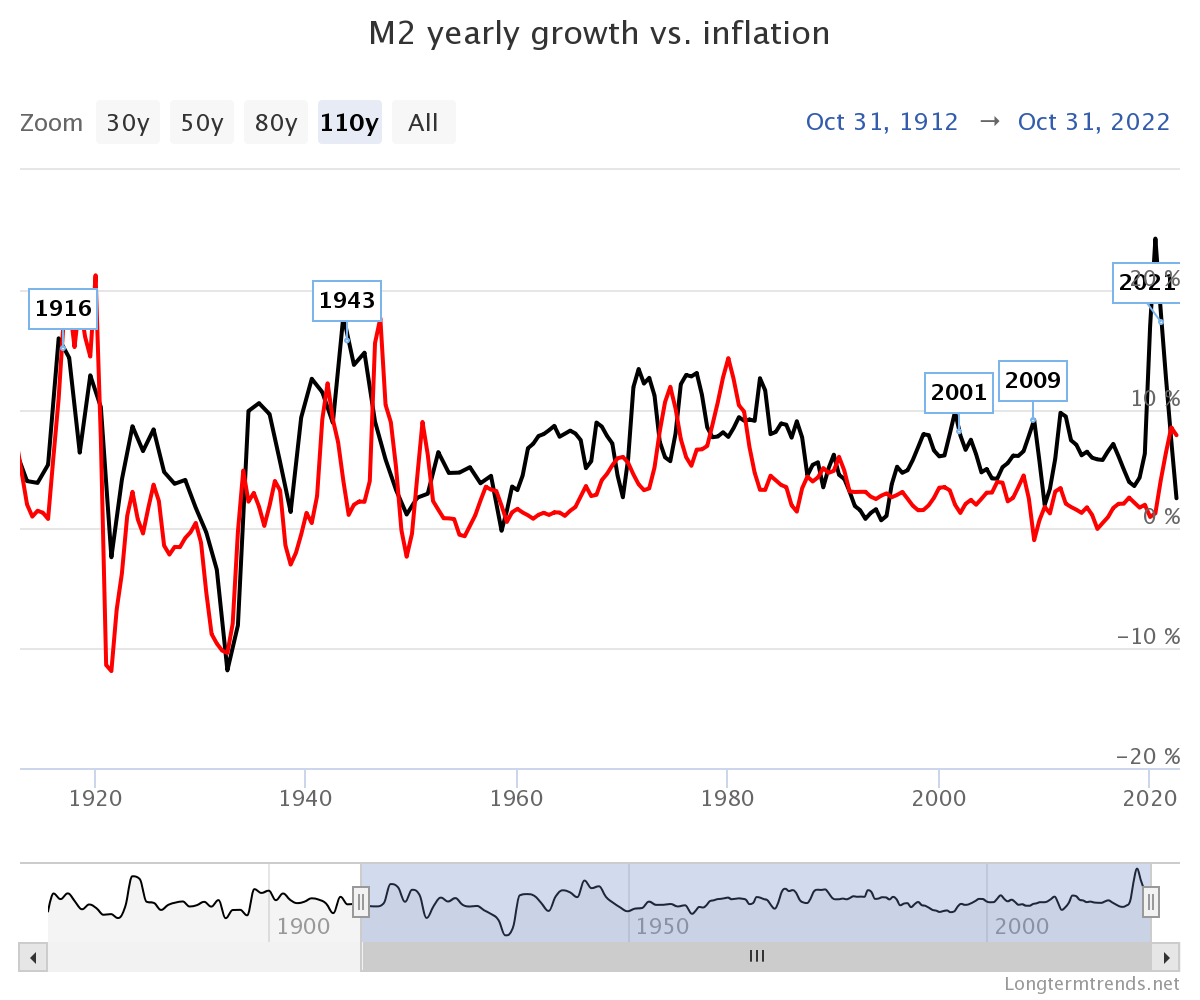

According to our thesis that money supply growth is a key factor in rising inflation, we should expect to see inflation rise during times when the M2 money supply expands. Which is exactly what we see is the chart below (and not just in the past few years, but during the early 1900s, the 1940s, and the 1970s as well).

Money supply growth rate - black

Inflation - red

Above chart from: https://www.longtermtrends.net/m2-money-supply-vs-inflation/

A small amount of money printing leads to a small amount of inflation; excessive money printing leads to the current situation we’re in where CPI at 9.1% is the highest it's been since 1981.

Again, inflation is multifactorial but occurs because governments can print new currency but they cannot print new electricity, oil, food, gold, silver, or bitcoin.

Commodities and goods and services aren’t actually getting more expensive, i.e.: they don’t require more labor or resources to produce, it's just that the currency we use to measure them is becoming worth less and less. Thus, it takes more units of the currency to purchase the same amount of goods and services as before.

The above situation begs the question: how do I avoid holding a currency that is being devalued by those who can create more supply by pressing a button?

Money is technology that evolves through time. In theory, this would suggest that it improves the longer it exists. At the very least, it has the capacity to. The evolution of precious metal into coins (and again into bank notes associated with an amount of gold) illustrates this.

In 2009 a new money called bitcoin was created which has properties that have never existed before in all of recorded history. This technological breakthrough is a bigger jump than that of scrap gold to gold coins - the invention has led to completely new properties of money for society to consider when evaluating which money is best, and therefore which should be globally adopted.

The new properties of money that weren’t possible before bitcoin are:

- Absolutely scarcity/non-debasable - is quantity of money fixed in supply regardless of demand for more units? Can someone artificially increase the supply of units?

- Non Confiscatable - is it possible to take your money from you?

- Censorship resistant - can you send it to whomever you want without needing permission?

I read history as the story of man encountering uncertain realities, struggling against his natural limitations, and passing knowledge to others in the form of written word and mentorship.

History is also the story of man making the same grievous errors over and over again. One of the critical errors he keeps committing is destroying wealth through the corruption of money.

Humans haven’t fundamentally changed in known history - only our technology and environment has. In the “Theory of Money and Credit” by Ludwig Von Mises, the author states currency debasement is an easy, indirect, and indiscernible way for the government to get the money it needs, without changing its spending behavior, or having to raise taxes.

So what does a government do when it needs money, doesn’t want to cut spending, and doesn’t want to raise taxes? They debase the currency. How do they do this? By printing more units of it.

Here’s a short history of monetary debasement, inflation, and negative side effects: https://www.goldandsilver.org/government-debasement-of-coinage/

Before we go too much further, one question to ask when looking at currency: how long do paper currencies that aren’t tied to gold last?

Paper currencies that aren’t tied to gold historically end up being worthless over a long enough period of time. See a list of all fiat currencies in use today here: https://www.worlddata.info/currencies

In the next part, we’ll actually ask the question: what is money?

What is money?

So, what is money, and why should you care?

Money is technology that stores energy. We spend our lives trading our time for money. Money, then, is our excess energy we store today to use tomorrow.

Money is essential, like air, water, and food. You can’t live without it. Good money stores your energy so you can have freedom in the future. Bad money loses energy over time, which costs you that same freedom in the future.

Money is any universally desirable piece of technology that stores energy.

We already looked at how money solves a very real problem of exchange rates in society and has value because both parties using it believe it does, but next we’ll look at a few important considerations for selecting one form of money over another.

If we agree that money is technology that stores energy and is essential for life, a few questions come to mind… for example, what is the best technology (money) to store our energy? Is there a type of money that can’t be seized by other people?

Let’s use our newfound knowledge of the function and properties of money to evaluate a few different forms of money to see which is best from a first principles perspective.

Question 1: What money holds energy best?

Should we store our energy in a leaky cup, or an airtight thermos?

New gold is created via cost intensive mining and refinement, but the amount of new supply added to the existing supply is slow, around 2% per year. There's a leak, but it’s small.

Compare gold to US Dollars or any other paper currency. When I look at the US Dollar chart, it has lost 97% of its purchasing power over the last 120 years (and this is actually not as bad as many other currencies).

The money supply expanded (using M1) by more than 80% since 2020 alone. This additional supply means that the value of the previous dollars are worth less.

With fiat money, the government can create more supply of it at the press of a button. This is a very leaky cup. One might say it is closer to a sieve than an actual cup. (I’m abstracting away a lot of the details here, but you get the point.)

Say we have [x] dollars we want to save toward retirement, ideally, we want to store our money in a system that has no leak. A leak in the system means we lose stored energy. Losing stored energy means we have to work harder than necessary just to maintain our current purchasing power (Red Queen Effect, anyone?).

It also raises questions of who controls how much energy is lost? And does the leak rate change frequently or infrequently?

Are you saving in currency or money? What is the opportunity cost of selecting the wrong money?

Question 2: What money can we actually own so nobody can take it from us?

Or, should we store our money in a cup someone else owns, or a cup that we own?

The idea behind gold is that you, the holder of the gold, are its owner. Presumably this is because only you know where it is located. This is a good thing in countries like Argentina, Greece, or others where bank deposits have been seized by the government.

It’s also the reason why many Argentineans I know prefer gold to paper money.

Let's define an important term: Fiat currency.

Fiat currency = any currency not backed by a commodity like gold or silver. It has value because the government says so.

Fiat currency = paper currency. It is far different from gold. With fiat currency, what you think of as money is really just ledger entries in a digital accounting system at the bank which is created at the press of a button.

Just imagine going to the bank and being told you can’t withdraw your own money. This is the cost of storing money in a location (or cup) that you don't control. Even worse, imagine finally being able to access it, only to learn it doesn’t buy as many goods and services as before.

Again, this is how inflation occurs: the government creates more supply of fiat currency units, which devalues the existing supply.

This brings us back to our leaky cup, which can continue to lose value while it's out of our hands and institutions deny us access to it.

This is how our two main questions intersect.

We want something both airtight and in our possession, especially during uncertain or unstable times.

Gold is better than fiat currency because you own it, can spend it how you want, and the government can’t print more of it and thus decrease your purchasing power.

Gold is unquestionably good money from most of the classical definitions and properties of money. But gold isn’t easy to transport physically which can lead to confiscation and limitations on who you can send it to, and it can be created by mining more of it as the price rises (relative scarcity, not absolute scarcity).

This is what I love about knowing history and watching the technological evolution of money across millennia… we moved from barter and trade -> gold metal scraps -> to gold coins -> paper bills that represented gold -> worthless paper currency that can be created at the press of a button -> electronic money with a fixed supply and an unchangeable monetary policy.

Bitcoin is the best form of money humans have ever had due to its monetary properties.

Bitcoin is initially an intimidating subject (at least, it was for me) because nothing like it has ever existed. It’s a bit like some things and a bit like a few others, but not like any one thing I can point to. That makes it tough to understand.

Fortunately, there are now courses (see resources below) you can take to learn about it through the lens of history, economics, technology, and politics.

It took me many hours on internet forums to actually understand Bitcoin but I can now confidently say the following:

I believe Bitcoin is the single most important technological innovation of our time.

Read the whitepaper here:https://bitcoin.org/en/bitcoin-paper

So what is Bitcoin?

Bitcoin is money. More specifically, bitcoin is digital money that runs on a network of computers that no one single person, or group of individuals, controls.

You can send bitcoin directly to people across the world via the internet without using a bank account. This means you pay less fees, can transact whenever you want, and can’t have your funds frozen.

Bitcoin is open-source so everyone can review it, and no one person, country, or business owns it. The Bitcoin network relies on advanced computers called miners to secure the network and verify transactions. Once transactions are verified they are recorded on a public ledger that anyone can review. The same encryption used in banking and the military is used to verify transactions.

Bitcoin is superior to other monies we have had in the past. This is due to its monetary properties. Bitcoin has many of the properties of money we outlined earlier (except for the established history as it is only 13 years old) and many of the ideal properties of money we introduced earlier, including:

- Absolutely scarcity/non-debasable - is the quantity of money fixed in supply regardless of demand for more units? Can someone artificially increase the supply of units?

- Non Confiscatable - is it possible to take your money from you?

- Censorship resistant - can you send it to whomever you want without needing permission?

Absolute scarcity:

Bitcoin is a fixed unit supply currency. There is a maximum supply of 21 million units. The Bitcoin network is set up so no one person or group can change the supply. Even though bitcoin can be volatile in the short term, the fact that nobody can create more makes it a good store of value over the long term. So to revisit the concept of where to store our energy, Bitcoin is better than a cup without a leak, it's an airtight container.

Non confiscatable:

Bitcoin doesn’t exist in an account with a bank, or a safe deposit box, or any physical destination where someone can take it from you. If you use bitcoin with best practices, most people won’t know you own it.

This is completely different from the fiat currency in your bank account or even gold and other precious metals you keep at a bank - both of which can be taken from you, especially when you need them.

Censorship resistant:

Should you be able to send money to family in another country, even if the government is restricting movement?

Do you believe you should be able to receive money from those who want to send it to you?

Do you think you should be able to move to any country you want and that your existing nation state shouldn’t be allowed to stop you?

Censorship resistance isn’t something most people value at first glance, but upon reflection, it is one of the most important qualities you can have in money. Just like free speech.

Remember, money is energy.

Money is also the language of value which helps us communicate what activities and goods and services are most important with other members of the world. When money is in the hands of man, it is impacted by human nature.

One of the mistakes we keep repeating throughout history is manipulating money, which then negatively affects levels of societal trust, price inflation, economic stability, vertical mobility, geopolitics, and ultimately global human prosperity.

By taking money out of the hands of man, we create a better world. One where we don’t have to trust that man will do the right thing, but rather one in which man is unable to do the wrong thing.

This is a fundamentally different world.

A trustless world has never existed before and bitcoin may be the best chance we have at creating that world.

Subscribe if you'd like to stay up to date and receive emails when new content is published!